Is Free Will an Illusion?

On the surface, this seems like an odd question to ask. Everybody feels like they have their own free will - whether it's a big decision like choosing their life partner, or a minor call like whether to keep reading this article.

But when you break down the neurological process of conscious decision making, there is a distinct lack of evidence for free will. Scientific theories on cause and effect - and philosophical theories about the self - frequently rule out any need for a conscious decision maker at all.

Shit.

But how can this be?

Put yourself in your dog's shoes. (Not literally. I'm assuming your dog doesn't wear shoes. And if he does, that's a whole different article.) Is your dog exercising free will? Does he willfully choose to sit on your lap or is he acting on instinctive and conditioned needs for bonding?

Perhaps you believe that conscious free will is limited to humans. Some people argue this because we have the ability to daydream and fantasize - to consciously weigh up the alternatives to our choices and therefore become responsible for our actions.

If so, is your free will present in every single moment? Or do you only call on it during critical decision-making times? How does it feel when your free will kicks in? Is free will the only explanation for your action?

Ok, enough questions. Time for some answers.

A Free Will Experiment

Hold your hand out in front of you. At a random moment, when you decide of your own free will, flex your wrist.

If you didn't do the experiment, then you chose inaction. There's your sense of free will. And if you did do it, the moment you flexed your wrist gave you a sense of free choice in the timing. It was your decision. Right?

Well, no. It really wasn't. In a moment I'll explain why.

Like Where This is Going?

Many people strongly resist the idea that free will is an illusion.

Not only does it appear to rob them of their personal achievements, it also sucks away their sense of originality. It implies their thoughts and choices weren't even theirs to begin with.

(They were. But we're saying the source is unconscious, rather than conscious.)

Ethically, it's a whole big mess of worms. Having no free will implies that we don't need to take responsibility for our actions. Murderers and rapists are suddenly off the hook. What kind of a crappy theory is this?

Philosophers have long sought to pull apart the issue. Unfortunately, even the deepest thinkers among the human race have discovered it isn't nearly as clear cut as it seems.

Determinism

Determinism is the original mechanical theory first taught by Democritus.

Many modern scientists and philosophers believe the universe is deterministic. Due to predictable laws of cause and effect, all future events are already logically determined by previous events.

In other words, the starting conditions of the Big Bang have already determined the entire future of the universe, down to the movement of every last hydrogen atom. Every single outcome in your life is inevitable. There is no room for your ego or your sense of free will to change things up.

This theory also says that, theoretically, mathematics could be used to predict everything in the future. In the land of science fiction, Isaac Asimov depicted this actually happening in his Foundation universe.

Isn't a Coin Toss Random?

In the spirit of destroying this argument, you might decide to make all your life choices based on a coin toss. Heads I stay, tails I go.

Surely this is random. And by acting on it, you'll send ripples of non-determined change through the universe.

Sadly, this won't work. Because even the result of a coin toss can be determined.

Give a computer the exact initial conditions regarding air flow, distance from the floor, position of the landing surface, impulse exerted on the coin, and so on. It will be able to predict the outcome of the toss.

Thus, the outcome of your seemingly random choice was always determined.

Even truly random events, such as the radioactive decay of an atom, do not create a free will loophole in determinism since there is no conscious influence present.

Indeed, a coin toss has stripped you of your free will.

What About The Quantum World?

What About The Quantum World?

Quantum mechanics defines probabilities to predict the behavior of particles, rather than determine the future with certainty.

But we mustn't forget that the human brain is composed of such particles - and their behavior is governed by the laws of nature.

Though we may (as yet) be unable to predict the future of our universe with determinism, this natural principle holds true.

Are Any Philosophies Pro Free Will?

Yes. There's metaphysical libertarianism, which is the polar opposite of determinism. It states: the fact that we are physically able to choose different outcomes denies determinism.

For me, this like saying that because I have a knife and my partner's pissing me off today, then I am capable of choosing to murder him.

But that's not in my pathology. Nor have I had any life experiences that incent me towards murder. There's no desire, no will. But libertarianism says there is - simply because I have a knife.

Sub-branches of this philosophy, known as non-physical theories, say we have a metaphysical mind or soul which overrides causality. It makes way for the core beliefs of most of the world's religions, such as the Christian God giving man free will, or the still widespread belief that we have eternal souls.

There's another philosophy which claims to allow for free will - and it's called compatibilism.

The philosopher David Hume favored this middle ground, which claims to make determinism and free will compatible. The theory states that humans, animals and even computers make complex decisions in a determined world. And this creates a good enough representation of free will.

Computers with free will? Just how crazy is this Hume fellow?

Compatibilists say that some deterministic processes are so chaotic that their outcomes that can't be predicted, even in principle. So will some things are determined, others simply aren't.

A compatibilist can say "I may die on June 4th, 2044. Or I may not." He is simply saying he doesn't know what the determined future will be.

Critics say this meddles with the definition of free will. There is a difference between having the freedom to act versus having the conscious volition that can change a pre-determined course of events. Immanuel Kant firmly disliked it - calling it a "wretched subterfuge" and "word jugglery".

What Neuroscience Says About Free Will

So the philosophers can't agree. Big surprise. Perhaps science can help us out.

Neuroscience gives us the opportunity to study the brain's biological processes that surround free will.

Remember flexing your wrist before as a demonstration of free will? I knew you would.*

Performing this voluntary action involves a lot of brain processes. To flex your wrist, activity begins in the prefrontal region, sending connections to the premotor cortex, which programs the desired action in the primary motor cortex. Instructions are sent out to move the wrist muscles and the flex occurs.

Scientists can identify which neurons are responsible for making this entire action happen from start to finish. And guess what? The conscious part comes after the unconscious part.

Meet Benjamin Libet.

*Cutesy determinism joke.

Libet's Experiment

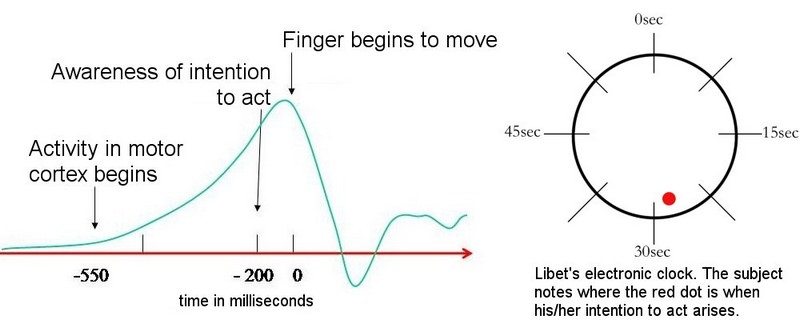

In 1985, Benjamin Libet decided to test whether a wrist flex is originated by a conscious act of free will.

He asked volunteers to perform the wrist flex action whenever they wanted, while measuring three events:

- A) The time at which they consciously decided to act

- B) The beginning of brain activity in the motor cortex

- C) The time of the wrist flexing action

Naturally, you'd expect the sequence of events to occur A, B, C. Free will. Motor neurons fire. Wrist moves.

But that didn't happen. And this is really, really weird.

The automatic brain activity fired first (B), then came the "decision" to act (A), then came the wrist flex (C). The timing separating these events was significant:

- B) At -550 milliseconds, the motor cortex fired

- A) At -200 milliseconds, the decision to act was made

- C) At 0 milliseconds, the wrist flex occurred

In other words, unconscious brain processes began planning the wrist flex movement more than half a second before the subject made any conscious decision.

In brain terms, that is a very long time.

The results of Libet's experiment are controversial. They suggests conscious free will as trick of the mind.

And yet, it makes perfect sense. The idea of a conscious decision arising before any kind of brain activity would be nothing short of magic.

It would imply consciousness comes out of nowhere to influence physical events in the brain.

(In fact, if the free will decision had arisen first, this would be evidence for a metaphysical mind or soul. Either way, this experiment was always going to start some arguments.)

Here's The Twist

Libet did not conclusively say that free will is an illusion. Because during the course of the experiment, he noticed something peculiar occurring.

Some subjects said they aborted the conscious decision to flex their wrist at the last moment. In these cases, the motor cortex activity fired but then flattened out again at -200 milliseconds.

This implies the existence of a conscious veto: the ability to consciously override impulsive or automatic actions if we choose.

Libet's conclusion was that consciousness can't create the wrist flex action, but it can act to prevent it. It's not free will. It's free won't.

Ethically, Libet is a hero. His experiment provides evidence for the condemning of criminals - who apparently failed to consciously veto their destructive impulses.

Unfortunately, there are criticisms of Libet's experiment. For instance, some doubt that we can generalize the results of trivial decision making to criminal behavior. How strong is this conscious veto anyway?

Final Thoughts

Ironically, most people accept that conscious free will exists.

(Yes, that is ironic. Because if you claim to consciously accept free will, you're also saying you could consciously deny it. Which is a paradox. Because you can't consciously deny the fact that you can't consciously deny things.)

Making life choices - like choosing your career or selecting a partner - arguably feel like expressions of your own desires, based on your experiences, your personality and your individual choices. This is how you live your life.

But what if all of these decisions are based on deterministic needs? What if your conscious justifications are always an afterthought?

Is it possible that all your choices are pre-programmed responses? That any sense of control over your life is merely an illusion created by consciousness? Passive Frame Theory says so.

"Everyone believes himself a priori to be perfectly free, even in his individual actions, and thinks that at every moment he can commence another manner of life. ...But a posteriori, through experience, he finds to his astonishment that he is not free, but subjected to necessity, that in spite of all his resolutions and reflections he does not change his conduct, and that from the beginning of his life to the end of it, he must carry out the very character which he himself condemns..."

~ Arthur Schopenhauer, The Wisdom of Life

So what do you make of this revelation? Assuming you choose to accept it. (And if you do, you accept it wasn't a choice at all, but an obligation out of unconscious fondling.)

Even if free will is technically an illusion, it is still a very powerful one. That feeling does not disappear overnight. I shed this notion a couple of years ago and it becomes increasingly easier to sit with. I continue to live as if free will exists - but knowing fundamentally that I'm guided unconsciously, not consciously.

It's no bad thing to accept that we're a series of biological processes and psychological responses. It's just weird to think at first. But if that's our reality - why fight it? We still don't know our futures even in a deterministic universe and we still don't understand ourselves well enough to predict what we might do next.

There are still surprises to be had without holding on to the illusion of free will.

Further Reading

A belief in free will touches nearly everything that human beings value. It is difficult to think about law, politics, religion, public policy, intimate relationships, morality - as well as feelings of remorse or personal achievement - without first imagining that every person is the true source of his or her thoughts and actions. And yet the facts tell us that free will is an illusion.

In Free Will, Sam Harris argues that this truth about the human mind does not undermine morality or diminish the importance of social and political freedom, but it can and should change the way we think about some of the most important questions there are in life.