Why Do We Dream? Modern Theories of Dreaming

Why do we dream?

Ancient civilizations saw dreams as portals for receiving wisdom from the gods.

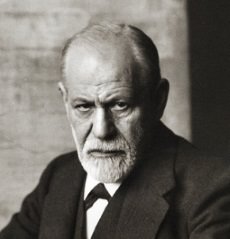

In Western psychology, Sigmund Freud famously theorized that dreams were the "royal road to the unconscious".

Modern theories suggest it's not as complicated as that...

Are we getting closer to understanding dreams?

"I want to keep my dreams, even bad ones, because without them, I might have nothing all night long"

~ Joseph Heller

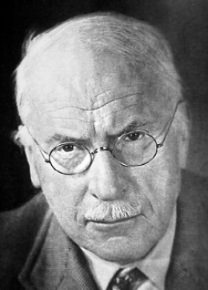

Freud on Why We Dream

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), also known as the father of dream research, gave psychoanalysis as one explanation for why we dream. But Freud had little understanding of the REM and NREM sleep cycles - and modern day dream research has pointed us to a number of other theories of dreaming.

Freud is best known for his theories of the unconscious mind. The controversial psychoanalyst said that our brain protects us from disturbing thoughts and memories by repressing them. Freud also believed that we are almost entirely driven by unconscious sexual desire.

If you asked Sigmund Freud "why do we dream?" he would say our dreams are a secret outlet for these repressed desires. In therapy, he used dream analysis to interpret the underlying language of dreams, which is very different from normal conscious thinking. I discuss this idea more in dream interpretation.

Every night when we sleep, we disconnect from our conscious thought processes. The lights go off and we're protected from external stimuli (like noise, temperature and pain). But our internal stimuli (like emotions and fears) are still rumbling around, seeking a way to be heard. And so dreams form.

Freud said dreams are a way to express unconscious emotions while we're asleep - otherwise we'd be constantly disturbed by them in our sleep and wake up.

So why do we dream? Freud said it was to protect our sleep.

J Allan Hobson

John Allan Hobson emphasizes the role of neurochemicals in the brain and random electrical impulses originating in the brain stem. Once stating that dreams are the random firing of neurons, he has since updated this view to say that dreams are the brain's cobbled attempt at making sense of them.

He later acknowledged the increased activity of the limbic system (a primeval part of the brain which produces emotions) during REM sleep. This served to give the meaning of dreams an emotional basis, rather than a random neurochemical one.

So, does this provide us with any psychological basis for dream interpretation? Was Freud right to suggest that dreams symbolize our repressed fears and desires? Do our dreams contain our darkest secrets just waiting to be unlocked?

Actually, Hobson believes Freud had it wrong. He may even have impeded our scientific understanding of the nature of dreams by propagating such ominous theories. Hobson is all for a psychological meaning to dreams, but just that it needn't be locked away under layers of secretive unconscious meaning.

Instead, Hobson takes a Jungian approach: dreams reveal far more than they hide - and can actually be highly transparent. However, it's difficult to link this conclusion to Hobson's biological explanation for dreaming.

But the theory does make sense. Next time you dream of being chased, isn't it likely that you are - metaphorically - running away from something in real life that's causing you anxiety? And if you dream of being pregnant - for a woman at least - is this a natural expression of your desire to have babies?

With simple interpretive analysis, dreams may not be so mysterious after all.

Why Do We Dream?

There are many theories of dreaming - some overlap with others and some are just plain bizarre. Dream research has given us these core theories:

We May Dream Because of Random Impulses

In 1977, Hobson & McCarley put forward some dream research that would seriously challenge Freud's dream understanding. They said that dreaming is the result of random impulses coming from the brain stem.

Using an EEG machine, the researchers were able to track the regular REM states of people during sleep. They used this data to form a predictable mathematical model and conclude that dreaming is a freak physiological (bodily) occurrence - rather than a psychological function.

According to them, the fact that we see images and hear sounds in our dreams is simply the brain's way of understanding noisy electrical signals. They said that dreams are random and meaningless.

However, many scientists point out that dreams often do make sense. In fact, they can follow very intricate plots, however illogical. This suggests that our higher brain is playing a role. Hobson's more recent theory (above) attempts to reconcile this by having a neurochemcial and an emotional basis for dreaming.

We May Dream to Organize The Brain

We may dream to de-clutter our brains. Every day we are bombarded with new information, both consciously (eg learning) and unconsciously (eg advertising).

This modern dream theory suggests dreaming is a way to file away key information and discard meaningless data. It helps keep our brains organized and optimizes our learning. This theory hasn't been proven by dream research. If it were 100% correct, our entire day would be replayed to us during our REM sleep!

Critics of this theory also point out that our brains are not the same as computers, and to draw a comparison to filing, processing and storage space is likely to be inaccurate. They also point out that although some of our dreams relate back to the waking day (Freud called this "day residue"), the majority of our dreams are not about real world events.

We May Dream to Help Solve Problems

A number of researchers think that dreams are for mental and emotional problem solving.

One scientist in particular, named Fiss, claimed that our dreams help us to register very subtle hints that go unnoticed during the day. This explains why "sleeping on it" can provide a solution to a problem.

Unfortunately, there are also arguments against this theory of dreaming. For a start, most people only remember a very small number of their dreams. So if our dreams contain important answers - shouldn't we remember them better?

We May Dream to Cope With Trauma

Dreams may be a way of coping with trauma. Based on the intensity of our emotions, we will generate dreams to cope with certain situations.

For instance, if you escape from a house fire and the experience shakes you up, chances are you will dream about it that night. The more traumatic the event, the more emotions are felt, and the more important it is to get over it. Dreaming about the fire will help you come to terms with what happened and prepare you for it ever happening again.

Of course, this doesn't explain why we dream of fantastic or mundane things - only that nightmares can be a kind of rehearsal for trauma.

Dream Analysis

Here are some more examples of how humans interpret dreams in different cultures around the world:

- Shamans use dreams to diagnose illness. It is thought that the unconscious brain has an awareness of malfunctions in the body long before the conscious brain. In this sense, shamans are psychoanalysts.

- The ancient Egyptians used dreams to make predictions about the future. They thought dreams were messages from the gods, which contained vital wisdom and prophecies.

- Similarly, people in the Western world in the 1900s used dreams to find game, predict the weather, and tell the future.

So Why Do We Dream?

Dream research offers many theories - but still no definitive or unifying answer to the question: why do we dream? Scientists generally seem to agree that dreaming is a form of thinking during sleep, even that may be the knock-on result of random electrical impulses.

It's generally accepted that dreams contain at least some psychological meaning, but this doesn't necessarily prove a purpose, such as problem solving. Overall, our scientific understanding of dreams is still quite vague.

In a way, Freud gave dreams an unfortunate legacy. He taught us to associate them with psychological problems and anxieties. But in reality, most of our dreams are healthy and engaging - aren't they?

If you'd like some further reading, try John Hobson's Dreaming: A Introduction to the Science of Sleep. John details his theories in some considerable detail and you'll learn a lot, no doubt.

Dreams are really a mixed bag. The truth is, science still doesn't have a complete answer. It may well be a helpful practice to remember your dreams and even interpret them.

And if you plan to have lucid dreams, your dream recall is vital.