A History of Dream Research

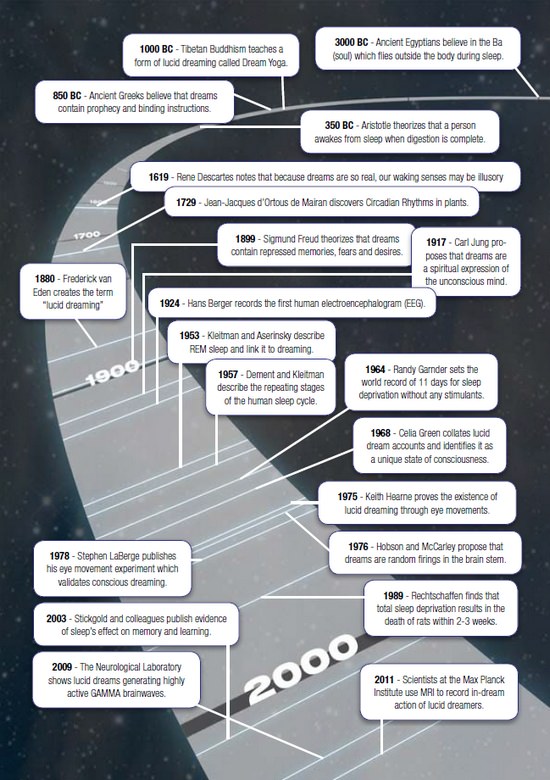

Dream research has long fascinated civilized man - from ancient theories of souls adventuring out of body, to modern day psychoanalysis and fMRI scans.

While ancient dream theories were mostly unscientific in their approach, they reveal our long-held desire to explore the hidden depths of the dreaming mind.

Today, dream research extends in many directions, and every year scientists around the world make new discoveries about the nature of the dreaming brain with biological, psychological and technological implications.

So how did we get here?

Ancient Theories of Dreaming

There is evidence dating back some 5,000 years, when the Ancient Egyptians painted pictures of the sleeping body (Ka) and the soul (Ba) hovering outside it, in the style of an out-of-body experience (which modern dream research has linked closely to lucid dreaming).

This tells us that people who lived thousands of years ago not only experienced OBEs and lucid dreams - but it was a common enough occurrence to have become a part of their culture, just like it is today.

We also know that, at least 1,000 years ago (and likely much longer) Tibetan Buddhist monks practiced a form of lucid dreaming known as Dream Yoga.

The monks used their dream world in an extraordinarily profound way - to study the depths of human consciousness and use it as a path to enlightenment. The art form can be learned to this day via works such as The Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep.

A Timeline of Dream Research

Philosophical Dream Research

In the 1600s, the French philosopher Rene Descartes propagated The Dream Argument. It states that our dreams provide evidence that our reality isn't actually "real" at all... The argument is based on two observations:

- First, that our senses in our dreams (especially lucid dreams) create worlds that can be so tangibly real and vivid, that our waking senses may also create a world that is illusory. How can we trust our judgment?

- Second, the fact that most people never recognize when they're dreaming, suggests our waking reality may function along the same lines. We may be living in a dreamworld and simply not becoming lucid while "awake"...

In the East, the dream argument is well known as

Zhuangzhou Meng Die (translated as

Zhuangzi Dreamed He Was a Butterfly). After he woke up,

Zhuangzi philosophized over whether he was a man who had dreamed he

was a butterfly - or a butterfly who was dreaming that he was a

man...

In the East, the dream argument is well known as

Zhuangzhou Meng Die (translated as

Zhuangzi Dreamed He Was a Butterfly). After he woke up,

Zhuangzi philosophized over whether he was a man who had dreamed he

was a butterfly - or a butterfly who was dreaming that he was a

man...

Indeed, this idea is woven throughout Eastern philosophy, and some schools of thought in Buddhism state that reality is not real in a very literal sense. As Chogyal Mankhai Norbu suggested: all of our waking sights, sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations are merely part of a much larger dream.

This line of thinking has infiltrated Western culture through movies like The Matrix. But this goes way beyond fiction. The Swedish philosopher, Nick Bostrom of Oxford University, has built a scientific theory called The Simulation Argument. The bold conclusion of his probability equations is that we are almost certainly living inside a computer simulation: we are the digital dreams of future human beings.

Modern Theories of Dreaming

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, is famous for his psychoanalytical theories of dreaming. He believed dreams are an outlet for repressed desires, that would otherwise wake us from our slumber. In Freud's view then, dreams exist to preserve our sleep.

In the 1970s, Hobson and McCarley did an experiment that suggested the origins of dreams are merely random electrical impulses firing from the brain stem. The researchers managed to track dreamer's brainwave activity using an EEG machine, and create a predictable mathematical model for this physiological process. According to their findings, dreaming is a bodily process - not a mental one.

The only gap in this theory (and it's a big one) is that dreams do actually make sense; so they can't be fully explained by these random electrical firings.

So Hobson extended the theory with a psychological basis for dreaming. And it flew in the face of Freud's theories of sexual repression. After the brain's cortex receives the random energy signals, the dreaming mind tries to make sense of them based on unconscious reasoning - i.e. lessons we have taught it from our experience of waking life. These "rules" aren't necessarily accurate, they are simply our perceptions of the world.

For example, you may believe that all men are murderous. This is great fodder for a dream about being chased by a male attacker. Yet the dream itself simply means you are running away from a source of fear. It's a common enough dream, made personal by our own personal fears, and not nearly as cryptic as Freud would have us believe. In fact, Hobson claims, our dreams reveal far more than they hide and we should shrug off "the mystique of fortune cookie dream interpretation".

Who Discovered Lucid Dreaming?

In our timeline of dream studies, we might ask who discovered lucid dreaming?

There is no single person responsible for "discovering" lucid dreaming. It is an innate skill we have evolved as human beings, such as being able to communicate through verbal language, or even think with an internal monologue.

It's a high-functioning ability, and we can currently only attribute lucid dreaming to humans. That's because to lucid dream, we need two things:

- To be able to dream - and remember those dreams. (Though research at MIT in 2001 found that even rats have complex dreams and are able to retain and recall long sequences of events while they are asleep.)

- To be self-aware and consciously reflective. (Only a handful of other species - among them chimps and dolphins - are thought to possess this skill, but no-one has yet determined if they can be self-aware while dreaming.)

Lucid dreaming is not as prevalent in the human population as the ability to communicate verbally, or think in words. But it has nonetheless penetrated our cultures for millennia and shone a brighter light on the mysterious dreaming mind.

In the Western world, the term "reve lucide" (lucid dream) was first identified by Marquis d'Hervey de Saint-Denys in 1867 in his book, Les Rêves et les Moyens de les Diriger; Observations Pratiques - which translates as Dreams and the Ways to Direct Them: Practical Observations.

The Dutch psychiatrist, Frederik van Eeden, experienced lucid dreams, and wrote in his 1913 book, A Study of Dreams:

"In these lucid dreams the reintegration of the psychic functions is so complete that the sleeper remembers day-life and his own condition, reaches a state of perfect awareness, and is able to direct his attention, and to attempt different acts of free volition... We are here, however, on the borders of a realm of mystery where we have to advance very carefully. To deny may be just as dangerous and misleading as to accept."

Half a century later, the British philosophical skeptic

Celia Green

recognized that lucid dreaming is a separate state of consciousness

- distinct from both regular dreams and waking awareness.

Half a century later, the British philosophical skeptic

Celia Green

recognized that lucid dreaming is a separate state of consciousness

- distinct from both regular dreams and waking awareness.

Green also published many accounts of lucid dreams, out of body experiences and apparitional experiences, and postulated that they all have something in common. Namely, that the subject's field of perception is entirely replaced by a hallucinatory one. Evidence for this hypothesis is presented in her book, Lucid Dreaming: The Paradox of Consciousness During Sleep.

As a result of this dream science and more, lucid dreaming has advanced our understanding of the dreaming mind, revealing an extraordinary capacity for conscious thought while asleep that is still not fully understood to this day.

Dream Science Today

For those who believe dream science is old hat - think again. Here is a smattering of just some of the recent discoveries in the field of dream research:

- The Neurological Laboratory in Frankfurt (2009) detected high frequency GAMMA brainwaves in lucid dreamers as they consciously accessed REM sleep. This provided further evidence that oneironauts access a greater level of consciousness when dreaming lucidly.

- The American Academy of Neurology (2010) used data from Mayo Clinic records to show a probable link between REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and Parkinson's Disease - up to 50 years before the dementia begins to show.

- The Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich (2011) used fMRI to detect dream actions of lucid dreamers from the outside world, such as clenching their fists. The same brainwave activity occurred when fist-clenching while awake, suggesting that the brain does not distinguish between the two states.

- The University of California in Berkeley (2011) also used fMRI to scan blood flow in the brain while subjects watched Hollywood movies. The blood flow analysis was then translated and reconstructed into moving images from YouTube clips to replicate what the subjects had watched. One day this technology could be used to record and reconstruct your dreams...